Roll Out The Barrel

St. Louis is and has been a beer-soaked town. In the city, on nearly every other block, the corner tavern may be found. It’s nothing new; beer has been flowing from local taps for 200 nears now. The difference between beer served a century ago and what is served today is that today’s brew is colder, subject to having gone through more processes, and, in many cases, lighter on the alcohol content. Yes, beer came in bottles Way Back When; even today, it is not uncommon to find discarded, mostly intact 19th century beer bottles, some beautifully embossed, in creek beds, home cellars, and at the bottom of old privies that once dotted every back yard.

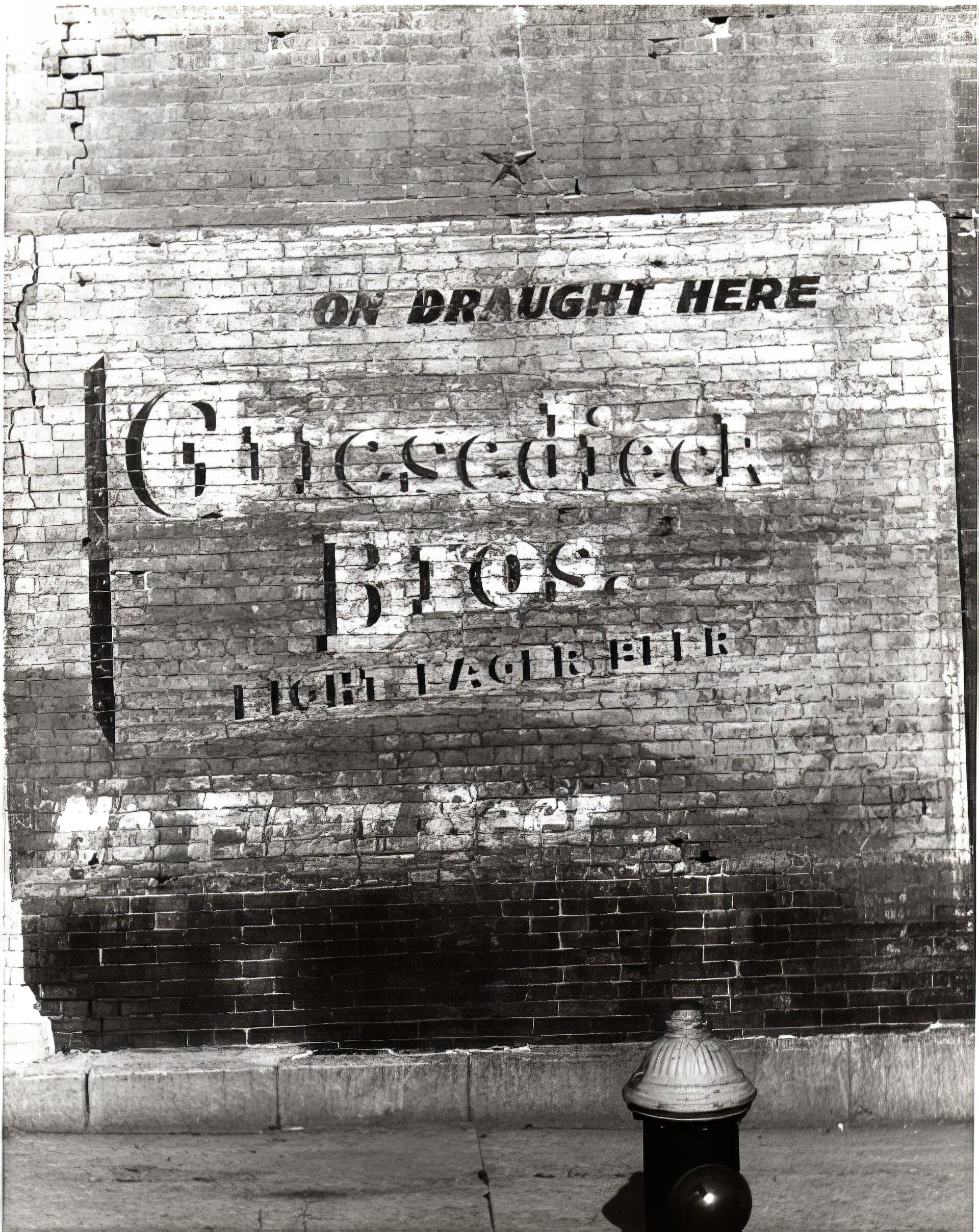

The earliest known brewer here was John Coons, who was putting out the suds back in1809, only five years after the territory was purchased by the United States. A year later, Jacques St. Vrain, one of the city’s original French residents and a former military officer, opened the St. Vrain Brewery. In the following decades, St. Louis’ collective thirst became even more prodigious. By 1860, a landmark year for beer production, the city had 40 breweries in operation. After that, the industry scaled back a bit. In my book, Mound City Chronicles, I list 18 local breweries operating in the year 1887. Most of them had names which are German in origin—the Anton Griesedieck Brewing Company, H. Grone Brewing Company, the Wilhelm Stumpf Brewery, Schilling and Schneider Brewing Company, and, of course, the one that would become world-renown, Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association. In fact, beer-making and beer-quaffing in St. Louis took a quantum leap only when the waves of Germans who emigrated here in the years prior to the Civil War became the Beer Barons and the men who worked their breweries.

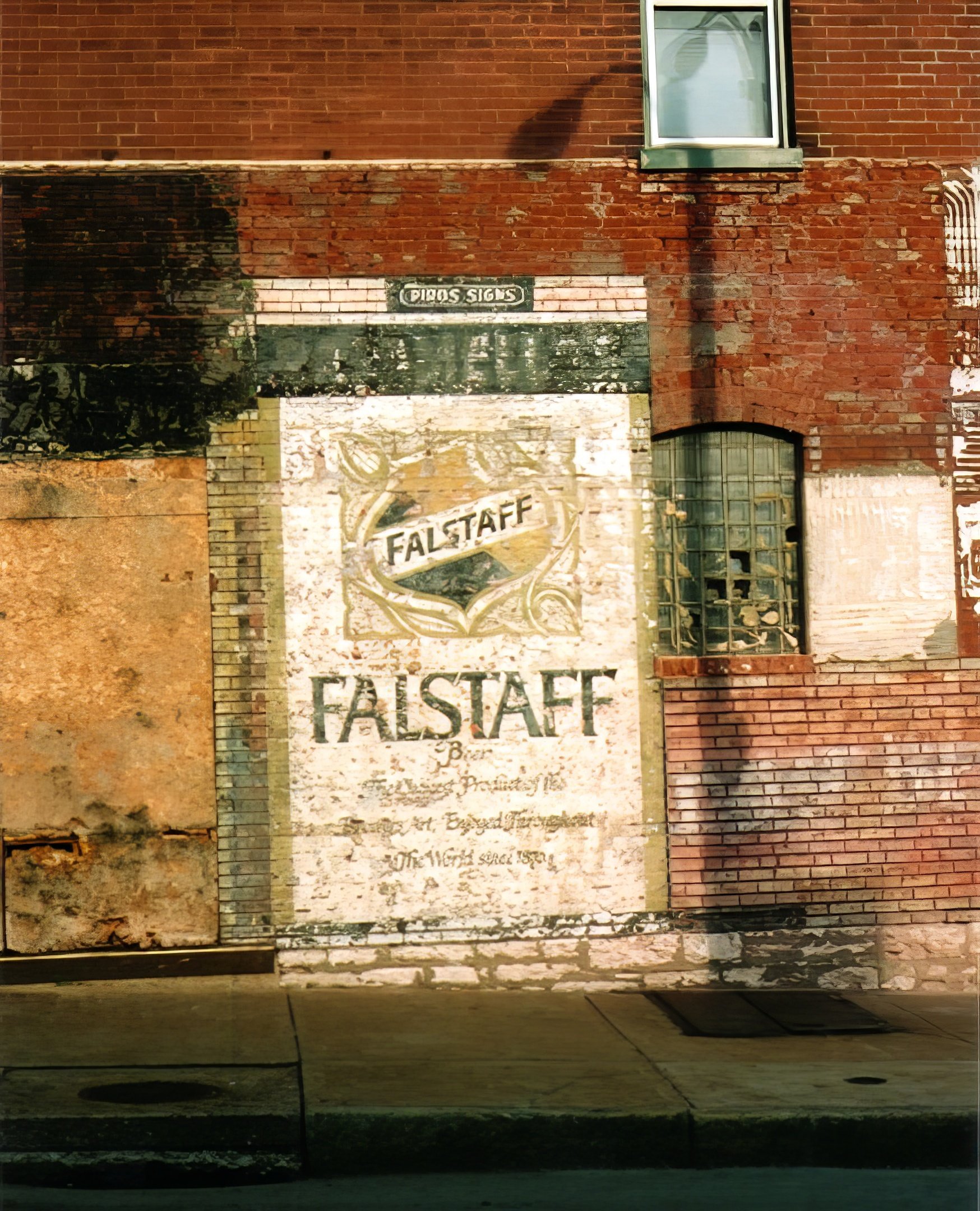

Of course, it all came to a crashing halt with the passage of the Volstead Act in1919. Prohibition caused the lay-off of hundreds, possibly thousands of brewery workers. Those breweries which did not close their doors for good tried to survive by making alternative products. Falstaff made brewer’s yeast, while other companies flirted with “near beer” in the form of malt beverages—The Louis Obert Brewery producing Trebo [Obert spelled backwards], and Anheuser-Busch bottling Bevo, actually, a fairly popular drink during the 14-year dry spell.

The party was over—or was it? In response to the now outlawed pastime of imbibing heady beverages, a black market sprung up. By and large, tippling was alive and kicking. It simply went underground—small batches of home brew fermenting in basements; larger batches of beer, wine and whiskey finding their way to speak-easies and private parties, organized crime overseeing the distribution. This bustling and clandestine trade ended with the repeal of Prohibition on April 7, 1933, a banner day for St. Louis watering holes, once again filled with working stiffs too long denied the opportunity for a cold one after work—or any time, for that matter. Appropriately, The Milton Ager / Jack Yellen classic “Happy Days Are Here Again” is associated with the repeal of Prohibition.

In 2011, as I write this, there are still signs of those once proud breweries around town. I speak of commercial signs, ads painted on the sides of brick buildings, faded yet legible after so many years of exposure. None of these beers are in production today, and, with the exception of Falstaff, they have not been seen on the shelves for over fifty years.

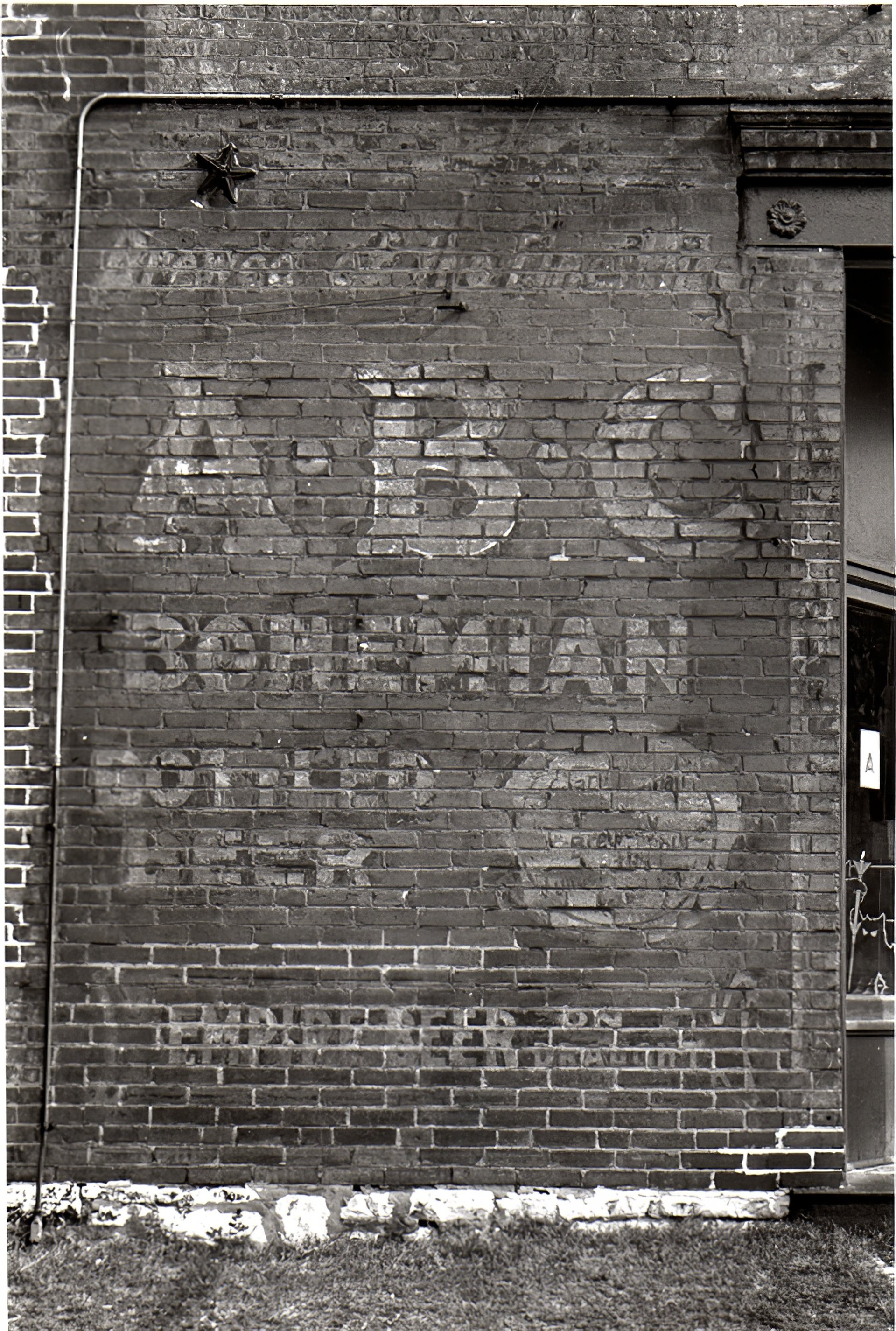

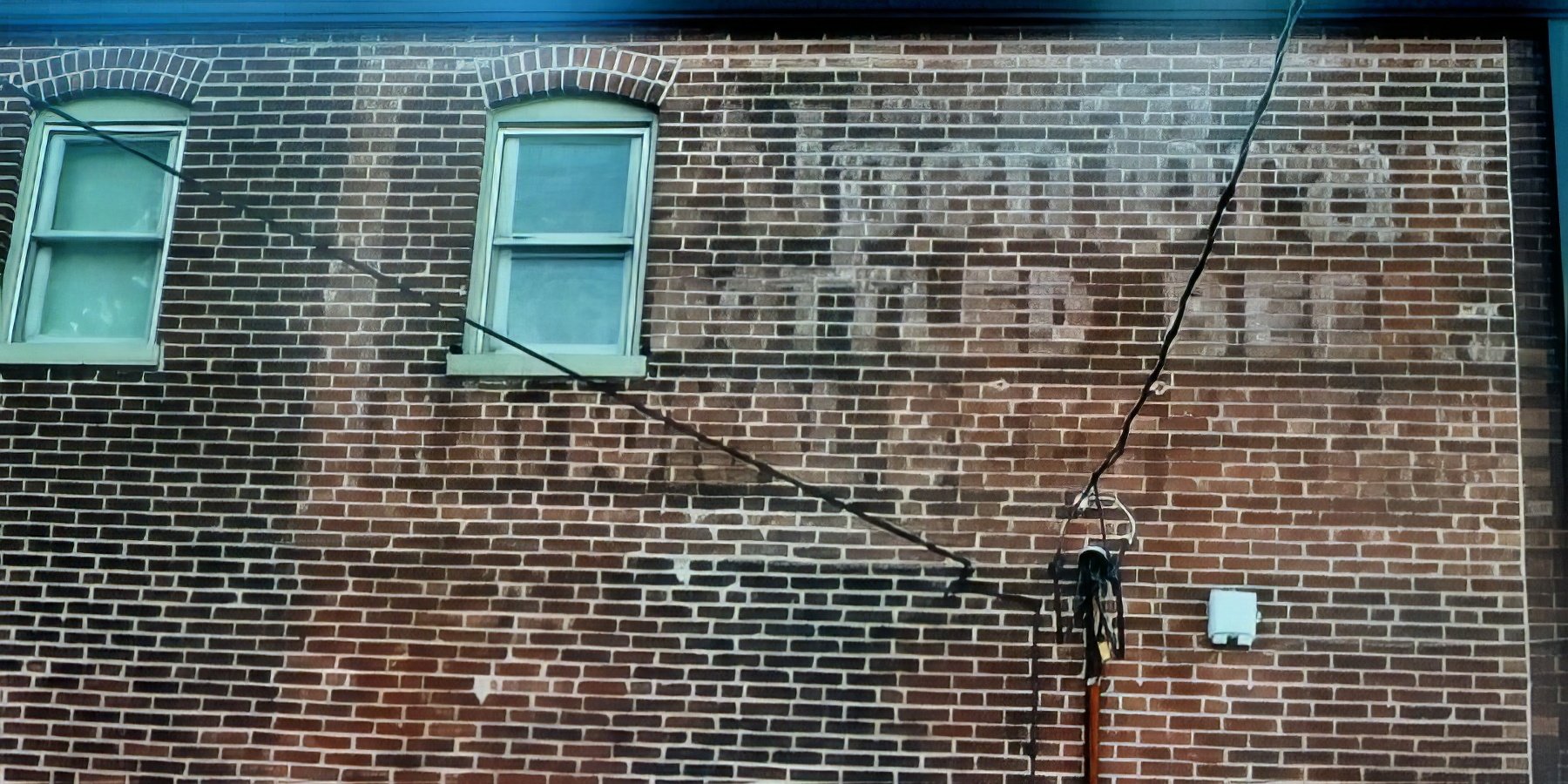

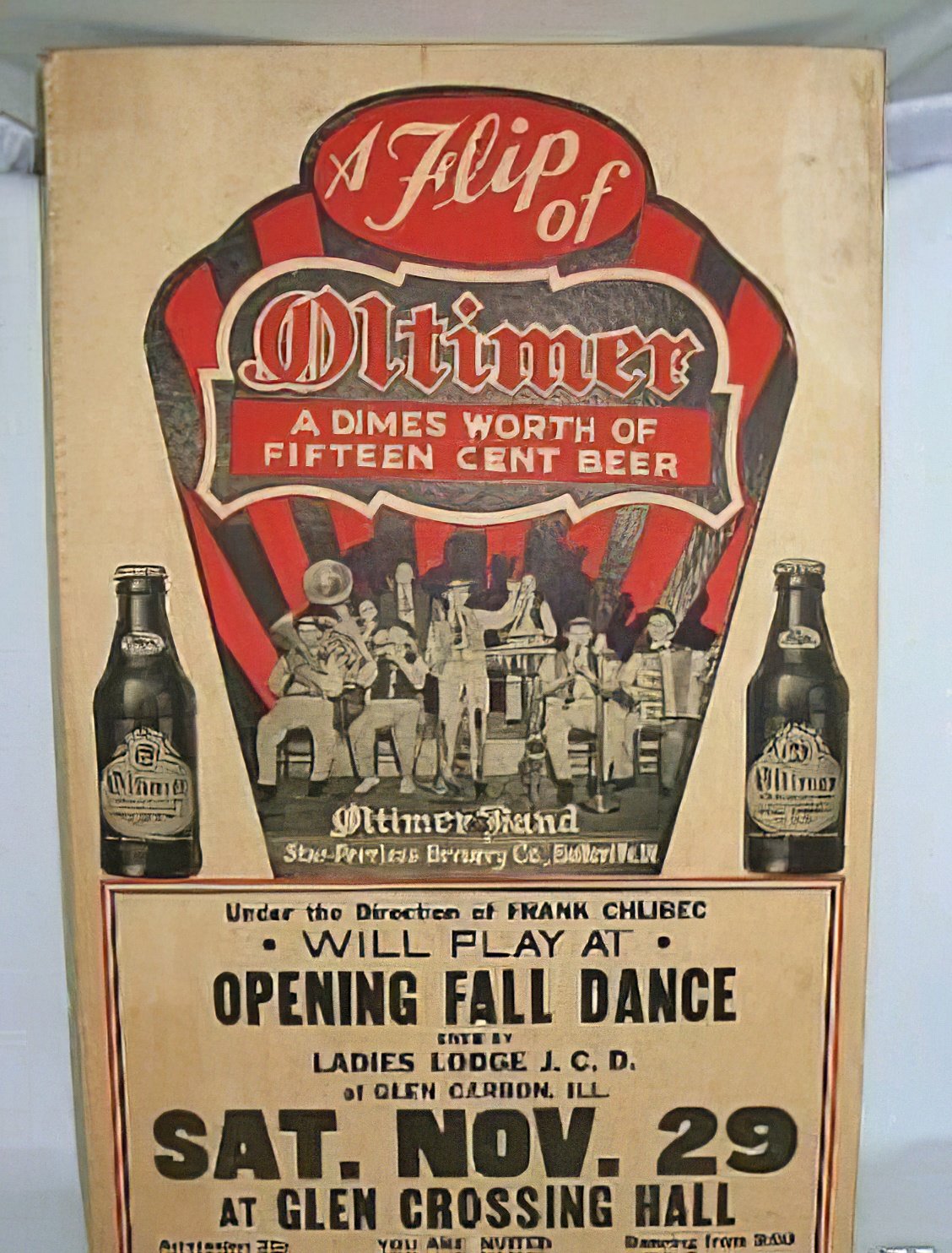

A large wall bearing an ad for A.B.C. Bottled Bohemian Beer [American Brewing Company] was photographed in the early 1980s on the south face of the former Rose’s On The Hill, now Lorenzo’s Trattoria. Likewise, the very faded ad for Green Tree Beer [H. Grone Brewing Company] was found on a quiet side street of The Hill neighborhood. Hyde Park Beer—“Seldom Equaled, Never Excelled”—was brewed in St. Louis and I have located three existing wall signs for the product: Edwards and Shaw on The Hill; Itaska and Delor on the Southside; and another, featuring a wee walking man, in a Northside neighborhood, the location of which I can’t recall. Columbia Brewing’s flagship product, Alpen Brau—“It’s the Tops!”—has two known wall signs in St. Louis, a pretty faded one at 39th and McRee, and a spot-on re-do located in the gangway of Seamus McDaniel’s Saloon, in Dogtown. Falstaff Beer has two decent examples in the city limits, one on North Broadway and another at Arsenal and Macklind, exposed as recently as 2009. Piros Signs, still operating in Barnhart, Missouri, had the contract with Falstaff to paint and letter all their out outdoor advertising. The last fading beer sign is found across the river in Illinois. Oltimer Beer was brewed by the Star Brewery in Belleville, which ceased operations in 1957. This large and busy ad is still apparent on South Main in Belleville, above what is now a hair salon. Oltimer Beer’s quirky slogan—“10 cents worth of 15 cent beer.”

For a definitive history of St. Louis brewing check out the richly illustrated tome by Henry Herbst, Don Roussin and Kevin Kious titled St. Louis Brews: 200 Years Of Brewing In St. Louis, 1809 – 2009.